TMS for Cognition / Attention / Memory Improvement

TMS for Cognition / Attention / Memory Improvement

Cognitive impairment is a prevalent symptom among people living with Multiple Sclerosis (MS), affecting approximately 50-70% of patients at some point during the course of their illness. These cognitive challenges can significantly impact daily functioning, leading to difficulties in memory, attention, and other cognitive domains.

At Shore Clinical TMS & Wellness Center, we specialize in using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) therapy to address cognitive impairment in people with MS. TMS therapy is an innovative treatment used worldwide to enhance cognitive function and improve overall well-being.

Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

Cognition involves the following mental processes:

- Concentration and focused attention

- Learning and memory retention

- Multitasking abilities

- Problem-solving and reasoning skills

- Planning, executing, and monitoring tasks

- Understanding languages

- Object recognition, assembly, and spatial judgment

Naturally, these cognitive abilities vary from one person to another. If these skills enable one to cope adequately with everyday life, they’re considered normal.

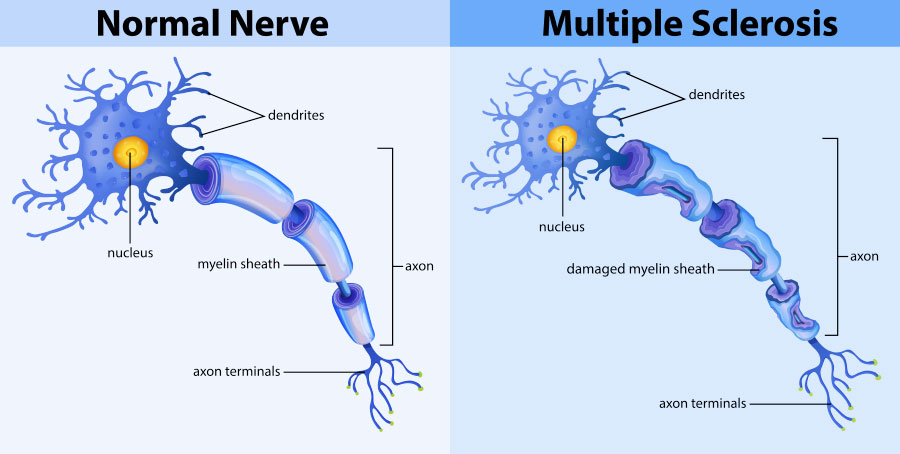

Cognitive impairment is a common issue in people with Multiple Sclerosis (MS), an unpredictable chronic disease impacting the brain and the spinal cord. The former affects attention, memory, and processing speed in approximately 45-70% of MS patients. Such cognitive challenges can significantly impact daily functioning and quality of life.

Symptoms of MS-related Cognitive Dysfunction

MS-related cognitive dysfunction can manifest in various ways, including:

- Difficulty concentrating

- Short-term memory deficit

- Reduced attention span

- Slowed thinking

- Trouble with problem-solving and decision-making

How Cognitive Impairment Affects Daily Life

Cognitive impairment in MS can pose challenges in various aspects of daily life, including work, social interactions, and self-care. People may struggle to keep up with tasks, experience frustration with forgetfulness, and find it challenging to maintain focus and attention.

How TMS Works for Cognitive Enhancement

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) offers promising results for enhancing cognitive function, including memory, attention, and executive function. Research shows that TMS therapy can stimulate specific brain regions associated with memory and cognition, leading to improvements in cognitive performance.

Recent Studies on TMS and Memory Enhancement

A 2019 study conducted at Northwestern Medicine revealed that TMS targeted at the hippocampus, the brain's memory center, improved memory in older adults with age-related memory loss. Participants showed memory improvements comparable to those of younger adults after TMS treatment.

Another study conducted in 2019, this time by Duke University School of Medicine, demonstrated that TMS improves working memory in both younger and older adults. Participants who received TMS performed better on memory tasks compared to those who received a placebo-like treatment. This suggests that TMS treatment may hold promise as a therapy for people with Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia.

These findings highlight the potential of TMS therapy as a non-invasive and effective treatment for enhancing cognitive function and memory in people with MS-related cognitive dysfunction and other cognitive impairments.

At Shore Clinical TMS & Wellness Center, we offer targeted TMS protocols designed to enhance cognition, attention, and memory in people with MS.

Our experienced team of professionals tailors treatment plans to meet the unique needs of each patient, providing personalized care and support throughout the process. With TMS therapy, people with MS can strive towards better cognitive function and a higher quality of life.